Re-evaluating our path to accessible air travel

Posted: 14 May 2025 | Kirk Goodlet, Sarah Cox | No comments yet

Kirk Goodlet, Vice President and Sarah Cox, Manager at InterVISTAS Consulting, explore the aviation industry’s path to accessible travel and reflect on what we need from regulators and government to deliver truly barrier-free access in aviation.

C: InterVISTAS

In December 2024, I had the opportunity to speak at the first ICAO Symposium on Accessibility in Civil Aviation. Jointly held by ACI-World and IATA, the event underscored the highest levels of commitment across aviation and government to improving travel for people with disabilities.

In both of their opening remarks, President of the ICAO Council, Salvatore Sciacchitano, and Canadian Minister of Transport, Anita Anand, reinforced the message that accessible air travel for people with disabilities is urgently needed. As Minister Anand stated, “for more than 80 years, ICAO and members have been working to make travellers feel safe and dignified and providing them with peace of mind.”

Accessibility in civil aviation cannot be separated from the human rights framework within which the United Nations, ICAO, and many governments situate it.

And, while it’s true that ICAO has played a fundamental role in shaping Member States’ regulations, our industry requires greater attention to how accessibility fits within ICAO’s framework, particularly its standards and recommended practices (SARPs) in Annex 9 – Facilitation. As Sciacchitano pointed out, “we have been working in the Year of Facilitation to create a better awareness of the relevance of facilitation in air transport – focus, of course, must be on safety and security.” He continued, “but facilitation is less known or less relevant… due to the complexity to implement the provisions of Annex 9.”

Join our free webinar: Revolutionising India’s travel experience through the Digi Yatra biometric programme.

Air travel is booming, and airports worldwide need to move passengers faster and more efficiently. Join the Digi Yatra Foundation and IDEMIA to discover how this groundbreaking initiative has already enabled over 60 million seamless domestic journeys using biometric identity management.

Date: 16 Dec | Time: 09:00 GMT

rEGISTER NOW TO SECURE YOUR SPOT

Can’t attend live? No worries – register to receive the recording post-event.

One of the things I have pointed out publicly is that accessibility must be seen as equal to safety and security. Accessibility in civil aviation cannot be separated from the human rights framework within which the United Nations, ICAO, and many governments situate it.

What aviation needs from ICAO

Over the last several years, I have participated in dozens of panel discussions, workshops, and have worked with airports and airlines to enhance accessibility in their facilities, products and services. What I have observed is a marked change in how accessible travel is spoken about in our industry and have welcomed greater emphasis on the topic at conferences and events. Indeed, there are now conferences exclusively dedicated to accessibility in air travel, which is a relatively recent change.

But aviation is a systems-driven industry. Take Annex 19 on safety, for example. Our industry is one of the safest precisely because of the standards and recommended practices that make their way into state regulation. Before Annex 19 was created in 2013, safety standards could be found in many other ICAO annexes: Annex 1 (personnel), Annex 6 (operation of aircraft), Annex 8 (airworthiness), Annex 11 (air traffic services) and Annex 13 (aircraft accident and incident investigation). As aviation became increasingly complex, ICAO recognised the need to consolidate safety management into a single, dedicated annex. This helped shift a culture from reactive to proactive and even predictive.

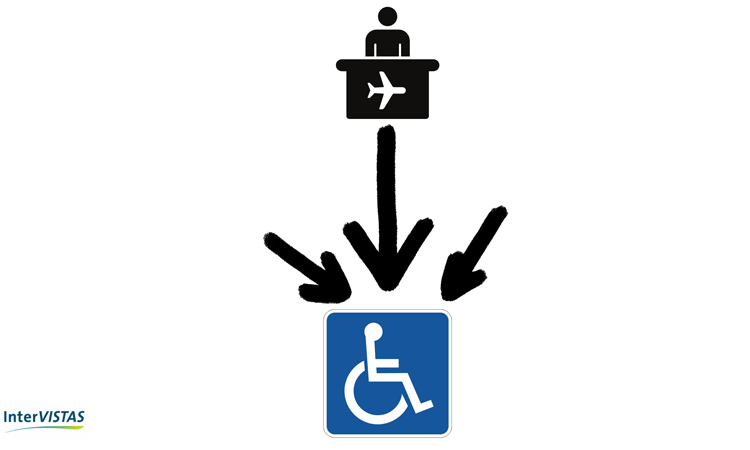

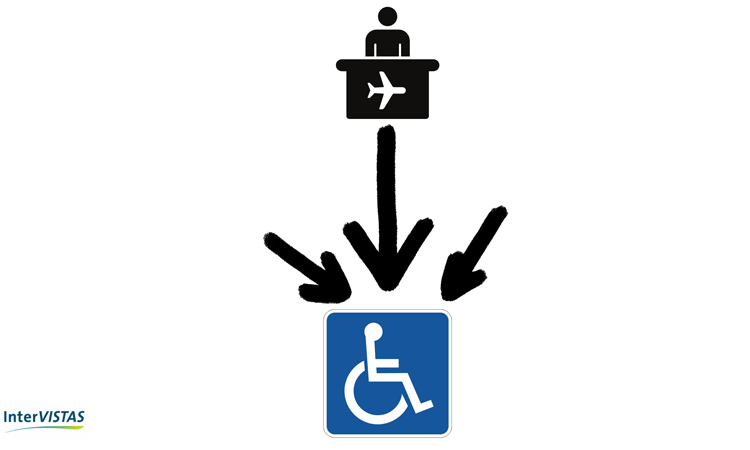

Limitations of Annex 9

The current model of assistance for passengers with disabilities is a top-down approach. It treats passengers with disabilities as passive receivers of assistance or aid, leaving the individual with little to no control over their travel experience. Although digital solutions to allocate staffing more efficiently are widely used, they do not solve the underlying problems of the service model and the ways assistance is delivered.

C: InterVISTAS

Annex 9 on facilitation, which was originally adopted in 1949, covers a wide-range of topics like electronic machine-readable travel documents (eMRTD), quarantine measures and human trafficking. Twenty-three years ago, in the 11th edition (2002), Annex 9 introduced new SARPs to address the treatment of passengers with disabilities.

In 2006, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) was introduced, which has sparked a global conversation about the need to support people with disabilities. Many governments have taken note along with the inclusion of disability as part of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The point here is that accessibility generally and accessibility in aviation specifically, are increasingly tied to fundamental human rights. No one expects to pay for a safe or secure airport experience – this is assumed. Yet, accessibility continues to be treated as a plug-in to solve a traditional problem, one of which is often constrained by operating costs.

If accessibility is considered a human right, then barrier-free travel must be elevated to the same level as safety and security.

If accessibility is considered a human right, then barrier-free travel must be elevated to the same level as safety and security. While well intended, the provisions related to mobility for people with disabilities need significant overhaul. Although Annex 9 introduced standards for passengers with disabilities in 2002, it’s no longer sufficient.

To achieve the right level of commitment from states, we need an Annex 20 to the Chicago Convention. This is needed to close the ‘strategy-to-operations gap’. This was my call to action at the ICAO Symposium in December 2024.

From strategic to operational-level change

In many organisations, tactical or operational-level discussions are seen as derogatory or less important. Corporate phrases and language reinforce this idea. Boardrooms are filled with statements like ‘keep it high-level’, ‘circle back’, or ‘take it offline’ that dismiss some of the important operational-level support needed to accelerate change in specific areas. And so, while we have the UN CRPD, state regulation, and other high-level commitments, there remains a disconnect between ‘what’ industry needs to do and ‘how’ industry can implement change. This disconnect is more pronounced when either state regulation doesn’t exist or whether executive-level understanding of accessibility is limited.

When speaking with focus groups, people with disabilities, and caregivers, common themes emerge related to inconsistency, unpredictability, and unreliability in services, products, and facilities during travel. Part of the reason for this is what I call ‘solutionising’. This happens when an airport introduces a separate product or service to address disability type rather than address the systemic barrier someone with a disability encounters in their environment. When combined with poor training, a lack of quality standards, or inadequate facilities, passengers receive different levels of treatment between airports, which induces anxiety and can result in undignified and even dangerous situations. A passenger who needs to connect via a second or third airport experiences this multiple times in a single journey.

ACI’s Airports and Accessible Travel: A Practical Guide (2024) provides some practical ways to take meaningful action at airports. This is an important document that should be required reading for airport staff and incorporated into training programmes.

The path forward

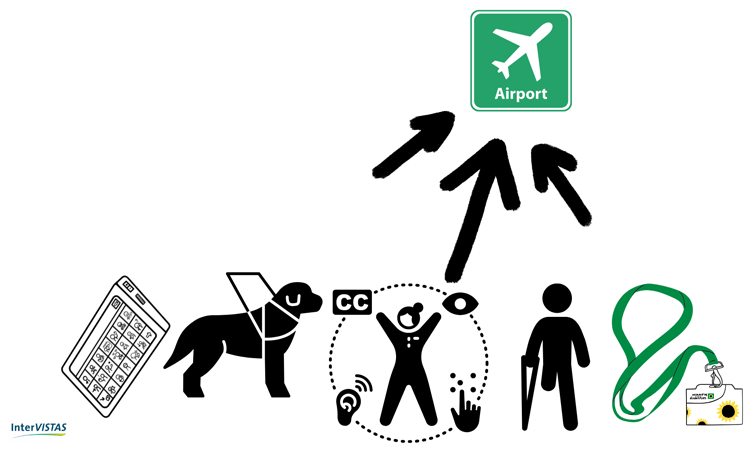

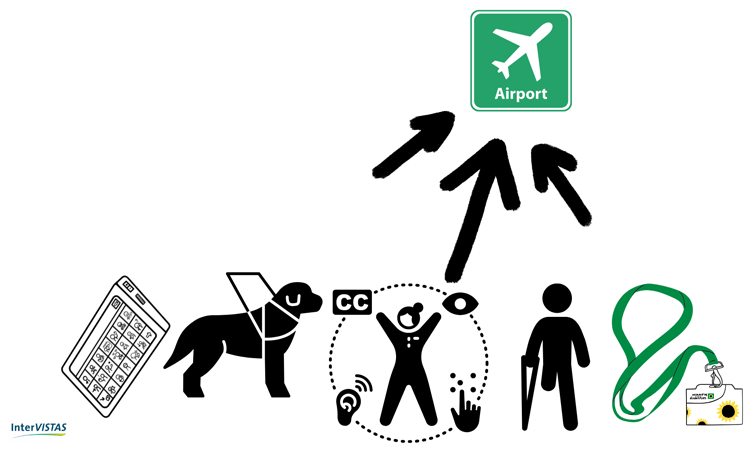

The term ‘passengers with reduced mobility’ (PRM) similarly reinforces this outdated model, closely associating a wheelchair with disability despite around 80% of people with disabilities having a non-apparent disability.

The industry prides itself on delivering great customer experience (CX) and its drive towards personalised – even hyper-personalised – services. But the degree of customisation available to passengers with disabilities lags significantly. Technology offers some promise to support more personalised journeys for passengers with disabilities, but it isn’t the solution. Part of the challenge here is the way in which passenger experience is co-managed and delivered across the ecosystem. Governance of assistance services continue to reinforce a top-down model, where all passengers requiring assistance are given a wheelchair. The term ‘passengers with reduced mobility’ (PRM) similarly reinforces this outdated model, closely associating a wheelchair with disability despite around 80% of people with disabilities having a non-apparent disability.

To deliver a more dignified and independent experience, we need the right strategic-level action with consistent programming and services for people at airports. The aviation industry stands at a critical crossroads. We can continue with incremental improvements or take bold action that reflects our commitment to human dignity and equal access. Annex 20 represents this bold action – a clear indication that accessible travel is not optional, but essential to aviation’s future.

c: InterVISTAS

Kirk Goodlet is Vice President at InterVISTAS Consulting, where he leads the global Accessibility Practice. Since 2018, he has co-led the global working group on airport accessibility as part of Airports Council International (ACI) World and is a member of Accessibility Standards Canada (ASC), developing federal standards on accessible wayfinding/signage and barrier-free travel. Ranging from accessibility strategy to operational-level change, his work helps organisations identify and remove barriers to equal access around the world. Kirk is a parent to a child with a disability and believes in a future in which everyone can travel with dignity and independence.

c: InterVISTAS

Sarah Cox is Manager, Accessibility at InterVISTAS Consulting. Sarah brings over 30 years of aviation experience with a strong background in terminal operations, passenger experience and accessibility. At Edmonton International Airport (YEG), she spent 17 years leading initiatives that improved efficiency, customer experience and accessibility. Prior to that, she worked at WestJet as a base trainer during which she was instrumental in developing and implementing accessibility training and standards.

Sarah has contributed to national efforts, including developing a standardised accessibility training module for the Canadian Airports Council (CAC), launching one of Canada’s first airport sensory rooms and chairing the CAC Accessibility Committee to drive sector-wide improvements.

Widely recognised for her leadership, Sarah is a national advocate for inclusive, accessible air travel.

Stay Connected with International Airport Review — Subscribe for Free!

Get exclusive access to the latest airport and aviation industry insights from International Airport Review — tailored to your interests.

✅ Expert-Led Webinars – Gain insights from global aviation leaders

✅ Weekly News & Reports – Airport innovation, thought leadership, and industry trends

✅ Exclusive Industry Insights – Discover cutting-edge technologies shaping the future of air travel

✅ International Airport Summit – Join our flagship event to network with industry leaders and explore the latest advancements

Choose the updates that matter most to you.

Sign up now to stay informed, inspired, and connected — all for free!

Thank you for being part of our aviation community. Let’s keep shaping the future of airports together!

Related topics

Accessibility, Passenger experience and seamless travel, Regulation and Legislation, Sustainability