Designing airport terminals to be dementia-friendly

Posted: 17 September 2020 | Joshua Jones - Weston Williamson + Partners | 1 comment

Joshua Jones, Architect at Weston Williamson + Partners, provides an overview of the challenges people with dementia face when travelling through traditional airports, and the techniques available to combat them.

Digital technology is rapidly changing the way that airports operate; streamlining efficiency and creating new possibilities for improving the end-to-end customer experience. By adopting a more human perspective, airports can spatially respond to the demands of the ageing population, in particular passengers with dementia.

By adopting a more human perspective, airports can spatially respond to the demands of the ageing population”

Airports are an intense stimulus of the senses, heightening both stress and anxiety. For people living with dementia, the situation is amplified, creating an isolating environment far removed from where they feel most comfortable. It’s important to understand how people-centred design can improve accessibility to air travel, considering that, globally, the number of people living with dementia is set to increase by 204 per cent to 152 million in 2050 (World Health Organisation, 2017).

Travelling through an airport with dementia

Dementia is a syndrome attributed to a progressive decline or deterioration in memory, concentration, communication, problem solving and behavioural changes, impacting an individual’s ability to undertake everyday activities. It is upon the removal of these memories that people with dementia lose their construct of selfdom, become dependent on others and unfortunately, through lack of societal awareness, become stigmatised.

By enabling customer‑focused virtual reality or 3D mapping of airports, passengers are able to have an immersive experience in advance”

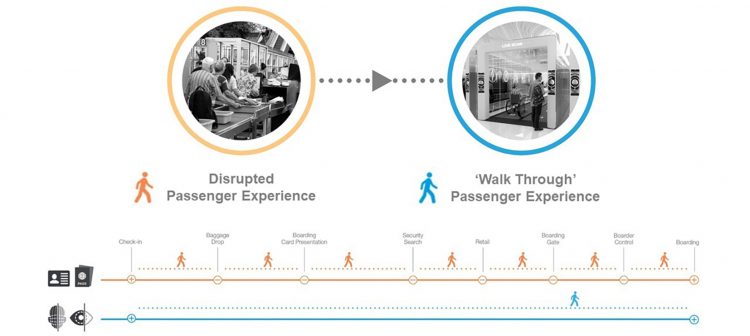

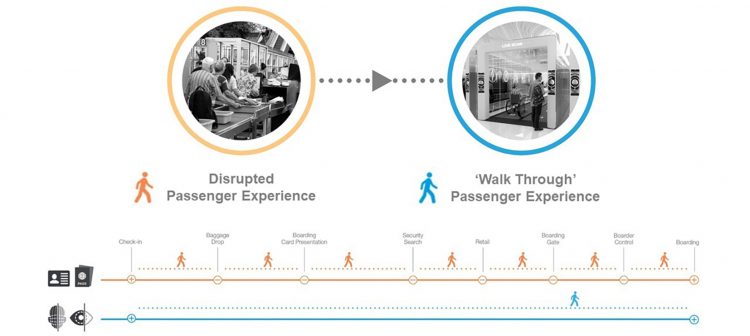

For passengers with dementia, leaving the security of the cultural milieu (the setting and environment one lives in but also feels secure) and entering the unknowns of the airport (vast spaces, buoyed by stimulus) is justifiably overwhelming. However, airports are beginning to tailor services to support customer needs and create a more informed passenger experience. Currently the airport experience from check in to boarding is disruptive – a series of necessary security checks that heighten stress triggers. By enabling customer‑focused virtual reality or 3D mapping of airports, passengers are able to have an immersive experience in advance, removing the insecurities of entering the unknown. Visitors are able to familiarise themselves with the check-in route, security processing and commercial offerings in advance; enabling a freedom to explore in a supportive environment whilst respecting boundaries and limiting access to certain security protocols.

Diagram: Security processing

Airport personnel

When cognitive ability declines, the built environment assumes even greater importance, becoming either a hindrance or an aid to retaining who we are. Having a central point of contact, booked in advance at accessible meeting points, creates that crucial passenger interface. Successful precedents, such as the Sunflower Lanyard, have demonstrated how a discrete solution has given visibility to passengers with hidden disabilities and allowed staff to locate them for additional support. By providing trained staff, who are aware that new environments can be disruptive to a person living with dementia, recognises the challenges the passenger faces and increases confidence.

The sensitive integration of additional data fields in the booking process would provide more detailed customer information to airport personnel on scanning the boarding pass, enhancing fast track security routes. Similarly, positive shifts towards biometric technologies allow a walk-through passenger experience which will reduce anxiety at key decision points in the process.

Airport infrastructure

Wayfinding is the manifestation of our navigation skills, our ability to orientate ourselves in the physical world and reach our destination through independent means. However upon its removal through dementia, it accentuates the decline of our self-worth and crucially, our identity. Identity is what structures our perceptions of place. People living with dementia have trouble with their visuospatial capabilities, their ability to perceive distances and objects in the third dimension. The syndrome therefore requires an enabling environment, one which can support the person. Duty-free shopping, for example, is designed to disorientate the observer and encourage interaction with the retail offerings. The misalignment of spaces impacts wayfinding performance, and the speed and accuracy of locating oneself within the terminal building layout is lost to spatial confusion. The ability of the human mind to look at ways to rationalise the situation is severely impacted and instigates anxiety for a passenger with dementia. It is of paramount importance to circumnavigate these spaces to a place of refuge. The introduction of augmented reality applications can help avoid this, and can be used to direct the passenger visually in real time and/or audibly with a dedicated help assistant. This enables the route to be predetermined ahead of a passenger’s visit or facilitate flexible assistance on the day.

Sensory technologies

A relaxed environment should be created without stigma, negative signage or connotations and with broad appeal”

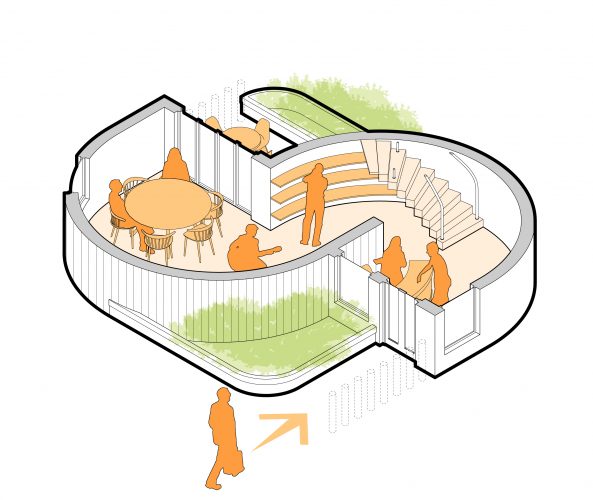

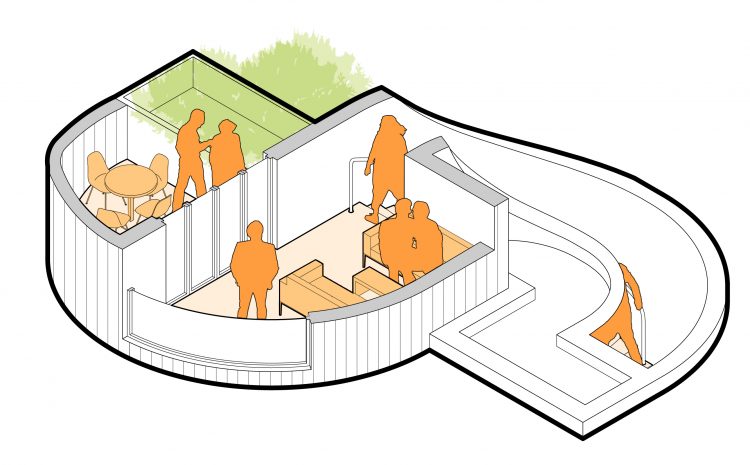

Airports can be the enablers, creating a new typology of sensory rooms in transport infrastructure. A flexible module solution is required, one that encourages widespread application and is responsive to space being at a premium. Construction techniques, such as prefabrication with embedded services, can be utilised to positive effect in these spaces. These techniques are designed to reduce the construction programme, achieve a higher level of quality tolerances, reduce material wastage and minimise concourse disruption within an operational airport terminal. The location in the airport is key, maximising inclusivity in the changing places so as to not isolate an important, growing demographic in society. A relaxed environment should be created without stigma, negative signage or connotations and with broad appeal. Key is exploring how to remove people from an overly stimulating environment by creating enclosed respite spaces within the open planned spaces, such as the departures lounge. The space can be pre-booked in advance to ensure the level of service and sensory stimulation is maintained at the correct level conducive for passenger respite ahead of their travel.

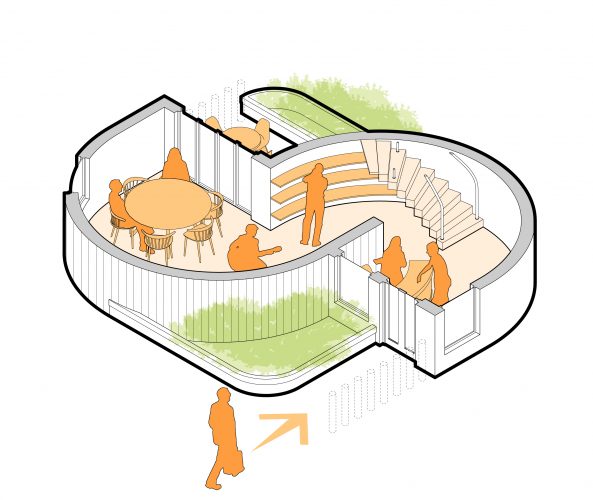

Jones’ Ground Floor plan for a sensory module

Adapting the airport space

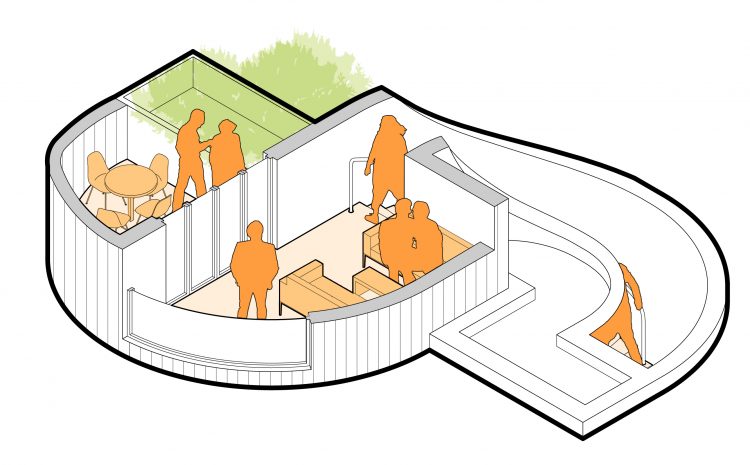

A person living with dementia achieves their desired sense of emotional security through the use of pre‑existing knowledge, stimulated through memory cues. This allows the individual to be settled but also thrive, confident in their surroundings and interaction with others. The domestic scale openings marking the thresholds into the space can provide a recollected comfort context within the terminal building scale. It is important for these spaces to provide exterior as well as interior views. Panic can be prevented by creating vistas to the sky or airfield, acknowledging the clinical proven benefits to wellbeing of a connection to nature. Daylight can also be utilised as a wayfinding device to orientate the passenger within the space itself. An organic, flowing form reduces the number of decision points and is designed to encourage wandering while ensuring legibility does not transcend the values of discovery. Zonal areas create environs for a person to thrive through social networks, created by communal activity areas and private reflection areas for personal and cultural activities, all of which are overseen by support staff. Using moveable partitions where possible gives the user control of extending or privatising these zones. External terrace areas at each level provide connections to the soundscapes of the concourse.

Jones’ First Floor plan for a sensory module

By creating dedicated sensory zonal areas to reboot or reset, users are surrounded by comforts that require the understanding of sensory stimulation. This is achieved by ensuring an executive feel through materiality, encouraging haptic memories (touch) whilst creating a customisable environment for echoic (soundscapes) and iconic (visual projections) memories. Integrating suitable seating space for aides and pager allocation services for individual travellers provides confidence that flights will not be missed. Airports can also ensure an equitable passenger experience by providing food and beverages facilities, prepaid to avoid the stress of transaction.

It is important to recognise how these provisions can give airports a unique selling point, resulting in enhanced customer demand and economic benefits from the ‘purple pound’. Airports can provide the enabling and supportive environment, that gives peace of mind to family and friends who would otherwise be concerned for the welfare of the passenger involved. Travelling should not be exclusive and should remain an opportunity for all, connecting people to both new and familiar experiences.

Biography

Joshua Jones, Architect at Weston Williamson + Partners, has worked extensively in the transportation and infrastructure sector. His speculative design portfolio includes a master planning piece for an aerotropolis at Birmingham International Airport. Currently, he is working on a technological and humanised exploration of how airport infrastructure can be better suited to an ageing demographic, specifically passengers with dementia.

Join our free webinar: Transforming Airport Security – Innovation, Impact, and the Passenger Experience

The landscape of airport security is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by evolving threats, technology, and passenger expectations. This webinar focuses on how AtkinsRéalis has been transforming security processes at some of the world’s busiest airports with smarter, more adaptive solutions.

Date: 4 Nov | Time: 14:00 GMT

REGISTER NOW TO SECURE YOUR SPOT

Can’t attend live? No worries – register to receive the recording post-event.

Issue

Related topics

Airport construction and design, Augmented reality (AR)/ Virtual reality (VR), New technologies, Passenger experience and seamless travel, Sensory technology, Terminal operations

i’m sorry to be negative by this, the biggest issue with this is that you can label people with lanyards, you can have secured areas, you can take away sensory issues in environments but unless the staff are effectively trained and worked with people who have dementia, then this will not work. Architects need to have massive knowledge of Dementia before designing spaces and this is why so many care homes are built that are not fit for purpose for people with dementia. Airports need to understand the issues from the persons point of view and giving them a 3d tour of a building before they arrive will not help them especially with short term memory loss. The areas and services must be built around communication, everything in dementia is around this and these areas and services must speak to the people and nothing in this article demonstrates the knowledge to make the environment communicate that its a safe, calm and fit for purpose place.