Changing times

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 2 October 2012 | Mike Willson, Managing Director, Willson Consulting | No comments yet

Much is happening in Airport Rescue and Fire Fighting (ARFF) circles at present. Proposed changes to the ICAO standard with the new Level C and apparent ‘dumbing down’ of existing Level A and B fire tests have caused considerable concern amongst airport operators. In addition, a few operators have started using Fluorine Free Foams (F3) for their operational response. They may be surprised, and somewhat confused, by unexpected results from recent independent testing in Denmark.

Substantial changes have been proposed to the ICAO standard fire test protocol. A new high performance Level C test is proposed to control air crash fires using higher performing foams and lower foam application rates. This could be beneficial and reduce the vehicles and mobile foam and water requirements affecting a range of category airports, but relies on a particularly low application rate of just 1.75 litres/minute/m2.

Of greater concern is the apparent ‘dumbing down’ of the existing ICAO Level A and B fire test protocols. This proposal suggests that instead of ICAO Level B approved aviation foams currently being expected to extinguish the Jet A1 fuel fire within 60 seconds, only fire control should occur within 60 seconds, with the extinguishment requirement extended to 120 seconds.

Much is happening in Airport Rescue and Fire Fighting (ARFF) circles at present. Proposed changes to the ICAO standard with the new Level C and apparent ‘dumbing down’ of existing Level A and B fire tests have caused considerable concern amongst airport operators. In addition, a few operators have started using Fluorine Free Foams (F3) for their operational response. They may be surprised, and somewhat confused, by unexpected results from recent independent testing in Denmark.

Substantial changes have been proposed to the ICAO standard fire test protocol. A new high performance Level C test is proposed to control air crash fires using higher performing foams and lower foam application rates. This could be beneficial and reduce the vehicles and mobile foam and water requirements affecting a range of category airports, but relies on a particularly low application rate of just 1.75 litres/minute/m2.

Of greater concern is the apparent ‘dumbing down’ of the existing ICAO Level A and B fire test protocols. This proposal suggests that instead of ICAO Level B approved aviation foams currently being expected to extinguish the Jet A1 fuel fire within 60 seconds, only fire control should occur within 60 seconds, with the extinguishment requirement extended to 120 seconds. So foams in the future will be required to extinguish the fire twice as slowly as currently, with no distinction from the current much faster and higher performance products in use today, as Level B has approved.

It appears there is no differentiation in terms of labelling or distinction between these new ‘second rate’ slower products, and the current faster and higher performance products. This could lead to significant confusion about the quality of products being supplied. Maybe some different new criteria will be required to avoid ICAO Level B being potentially less reliable as a quality marker after 2013, if these current proposals should become accepted.

Reducing test variables

Testing experts have apparently advised the ICAO Rescue and Fire Fighting Working Group (RFFWG) who are recommending these changes that; “a more consistent method of testing would be to keep the branch pipe or test nozzle static, to focus on control of the fire, i.e. to allow flickers and to introduce independent accreditation of performance testing.” But how will fire control be defined? Will having an accreditation inspector watching, help eliminate this variable? Surely one person’s 90 per cent control is another’s 85 per cent? It is all very subjective and difficult to spot the exact time a specific control time is achieved even when radiometers are used, because fire and its control is such a dynamic, rapidly changing event. Such fire control can happen surprisingly quickly, but may then take a long time of continued foam application, and burning, before extinguishment may or may not occur. Does that mean it is good foam to rely upon in an emergency? Does that make it better than one which repeatedly controls and extinguishes the fire within 60 seconds?

Whatever agreed control time may be used, what assurance is there that the foam blanket cannot flashback, before final extinction occurs? Surely that is why final extinguishment has been such an important measure to date, it clearly demonstrates that the foam has done its job, and has the capability of doing so in most emergency situations.

Is Fluorine Free Foam (F3) a credible replacement?

Some airports have opted to move away from fluorochemical AFFF foams altogether, even though extensive fate and behaviour research over the last 10 years has proved that the alternative fluorotelomer surfactants, especially the short-chain C6 versions currently used in AFFF, AR-AFFF, FFFP and AR-FFFP foams, although still persistent, are neither bio-accumulative nor toxic. They are considered by the US EPA and UK Environment Agency to be safe for continued use in emergency situations.

A few operators have chosen to rely on F3 alternatives for all their operational emergency foam response, based on some leading products gaining ICAO Level B certification, but questions and concerns remain over their reliability, variable performance, sudden flashbacks, viscous nature which has caused some congealing of proportioning systems, plus fuel pick-up issues. This can lead to hydrocarbons by-passing fuel separation systems and causing potential pollution incidents.

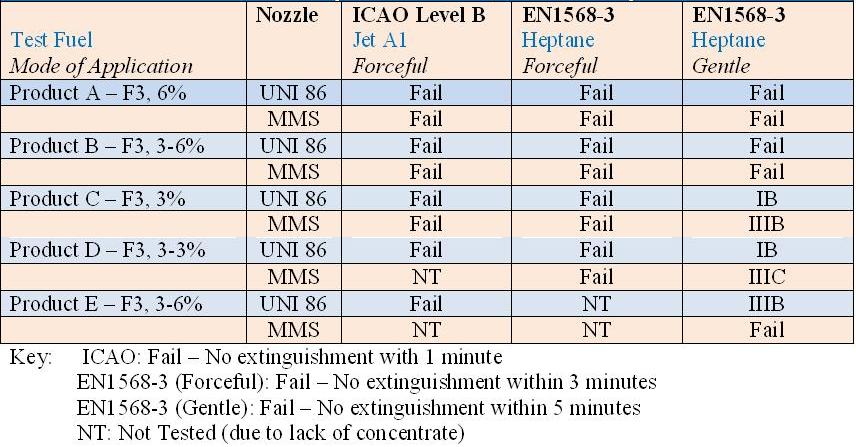

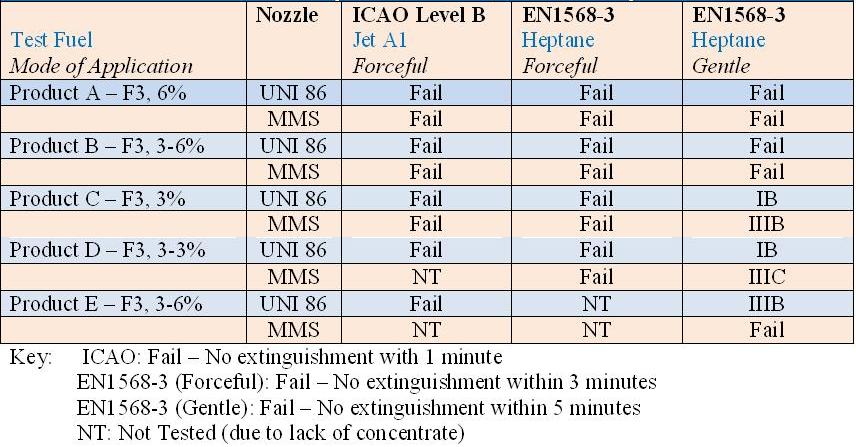

Interesting independent research has recently been conducted in Denmark, witnessed by the well-respected Consultants Resource Protection International (RPI)2 and explained by Hubert, Jho and Kleiner in a recent Asia Pacific Fire magazine article1. The unexpected results (see Table 1) throw a further twist into the complexities of this area. This full RPI report can be viewed on the International Airport Review website www.internationalairportreview.com or via www.dynaxcorp.com.

Table 1: Summary of Test Results, Denmark, May 2012

Four F3 foams from three different manufacturers were sourced in sealed containers from the marketplace. All were less than 12 months old. All four were claiming ICAO Level B performance approval, and four claimed EN1568 fire test requirement compliance. These four foams and a developmental product were all tested against the current ICAO Level B and EN1568 fire tests over four days in May 2012. The ICAO Level B protocol allows the option of moving the nozzle horizontally from its fixed position, but this was not undertaken in an effort to minimise variability, and enable a direct comparison between test results.

Failures caused by persistent edge fires

None of these F3 foams extinguished the Jet A1 fire within the current ICAO requirement of 60 seconds. None even came close. The best result was extinction in one minute, 24 seconds but the worst did not extinguish even within two minutes during these RPI tests, yet is currently approved to ICAO Level B. Why are we getting such divergent results, when three of these foams have previously clearly passed this test? Why are they all being beset by persistent edge flicker fires that are preventing them from achieving acceptable extinction? Moving the nozzle probably helps, but should it make so much difference? If so, should it not become a standard well defined part of the standard test, to further reduce variability and facilitate direct comparisons?

It is well known from a variety of other test work on F3s that extensive and rapid reinvolvement can occur, when small flames or incandescent materials act as a re-ignition source to fuel vapours that can hang above the foam blanket, as it deteriorates. Also complete re-involvement of the test tray has occurred within 60 seconds. The high hydrocarbon surfactant levels present in F3 foams, and lower quality AFFFs with little protective fluoro – surfactant content, make them particularly vulnerable to these undesirable effects.

Concerns that the UNI86 branch pipe specified by ICAO actually delivers more stable but stiffer foam (typical expansion ratios 8-10) than most practical foam nozzles being used by ARFF Services around the world, encouraged this project team2 to conduct re-testing of three products with a modified US Mil F spec nozzle (MMS), set to deliver an identical flow rate but more fluid foam quality (typical expansion ratios 4-5), better aligned to typical nozzles being used in the field.

The product which did not extinguish previously with UNI86 in these RPI tests2, extinguished slowly in 1 minute 58 seconds with this MMS nozzle, possibly because it was delivering a more fluid foam blanket. Confusingly the reverse occurred with the other two products tested with the MMS nozzle, where control times were actually extended, and both products then failed to extinguish. It is clear overall that with a more realistic nozzle the performance got worse. Each foam that extinguished the fire went on to pass the five minute burn back test, which did not seem to be a problem for these foams with either nozzle.

So why did these F3 foams struggle so much to extinguish this test with either nozzle at an independent venue, when they have clearly passed previously with the UNI86 during other tests? Does moving the nozzle make so much difference? Is this standard open to slightly different interpretation perhaps, by those conducting the tests, or are differences occurring in the fuel being used? Is it inherent batch to batch variability in the concentrates, or some other factor that is causing such long extinguishment times? Certainly this is a worrying situation for any operators already using these F3 products. Further research work is on-going to try and better explain why these results seem so variable.

Gentle application

A review of the EN1568 RPI test results2 also delivered surprises. No foam tested with either nozzle achieved a forceful application 1A rating. Unexpectedly when the MMS nozzle was used, control and extinguishment times extended with all products tested. Only three of the five products gained an EN1568-3 gentle application class rating. Does this mean that F3 foams are just not suited to forceful application and should perhaps be labelled ‘Suitable for Gentle Applications Only’? Where does this leave those few ARFF Services relying on an F3 foam concentrate to meet every Class B hydrocarbon hazard on airport, including potential bulk fuel storage tank and bund fires? Will they need to increase their foam application rates to gain the required performance levels? And if so, by how much? Or will they need to use some fluorotelomer based concentrate for these more demanding fire scenarios? What are the implications for their vehicles, crews and response times?

These tests also showed that even under gentle application conditions, some F3 foams failed to extinguish when the more typical MMS nozzle was used.

Conclusions

Proposed changes to ICAO Level B would seem to be ‘dumbing down’ the current requirements, which would allow currently unacceptable products to be accepted for ARFF applications, in future. This could have adverse impacts on the safety of fire-fighters, and other rescue personnel.

Recent independent testing in Denmark2 evaluated four leading F3 products against the ICAO Level B and EN1568-3 fire test standards to assess how they performed. Surprisingly all of the F3 foams tested failed the ICAO level B test by a substantial margin. None of these foams passed the EN rating for forceful application, and only three achieved a gentle classification. This raises serious concerns about variability, reliability and suitability of F3 products for both aviation and other forceful applications in future. Persistent edge flicker fires prevented extinction occurring within the required constraints of both protocols. Perhaps this is a consequence of removing the protective fluorochemical presence from these foams.

Proposals to adopt fire control as the primary ICAO assessment focus in future, while doubling the required extinguishment time, could be making potentially dangerous assumptions about the ability of F3 foams to avoid sudden flashbacks and re-involvement. It is clear from these Danish tests that product behaviour exhibits varying intensity edge flicker fires, before final extinction may, or may not be achieved.

References

1. Hubert, Jho, Kleiner, 2012 – Independent Evaluation of Fluorine Free Foams (F3) – A Summary of ICAO Level B and EN1568 Fire test results – Asia Pacific Fire, issue 43, Sept. 2012

2. Resource Protection International, 2012 – Fluorine Free Foam (F3) Fire Tests , Falck Nutec Training Centre, Esbjerg, Denmark, May 2012 Ref: P1177 – www.dynaxcorp.com and www.internationalairportreview.com

About the author

Mike Willson (BSc hons., MCIM) has over 25 years’ experience in the fire industry across many sectors including aviation and bulk fuel storage, much of it involved as a technical specialist on Class B foams, their application and associated foam delivery systems. Mike has been deeply involved in their product development and testing for many years, and has co-ordinated several emergency foam responses to major incidents worldwide. He also has a deep understanding of fluid transfer systems, large capacity monitor systems and the special hazards associated with liquefied gases, particularly LNG.

As a UK expert, Mike was heavily involved in the UK Government’s strategy review on PFOS (PerFluoro – Octanyl Sulphonate) and was instrumental in helping them take a practical and workable approach for the whole fire industry.

Mike also contributed to the European CEN Standards Committee by helping develop the recent fixed foam fire fighting systems standard EN13565-2:2009 which involved some ground breaking work on bund protection, LNG and bulk storage tank protection.

Four years ago, Mike emigrated to Tasmania and set up Willson Consulting where he provides technical consultancy fire protection advice, training and site surveys. He also focuses on environmental areas like project managing a State-funded green tourism project, helping smaller businesses save on energy costs and other sustainability projects.