Aviation starts on the ground

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 17 November 2016 | Tim Meagher (Ground Operations Inspector: Civil Aviation Safety Authority of Australia) | 1 comment

As the area of ground handling and the subsequent supply chain becomes ever more complex, Tim Meagher, Ground Operations Inspector with the Civil Aviation Safety Authority of Australia, discusses how airports and airlines must remain vigilant to make sure risks are identified and eliminated, ultimately to ensure the safety of both staff and the flying public.

The ground operations environment is becoming increasingly complex in nature. The emergence of modern supplier relationships has resulted in significant change for the aviation ground handling sector, involving an increase in airlines that outsource their ground handling activities. With the emergence of new suppliers and more niche service providers there is a changing of the supplier landscape that requires sophisticated management.

IATA conservatively estimates that at least 50% of ground handling activities at world airports are undertaken by outsourced providers. In all likelihood this number is even higher. In addition to this even when airlines do self-handle it is increasingly through separate corporate entities that operate at arm’s length from the parent company, in a similar way to a third party provider.

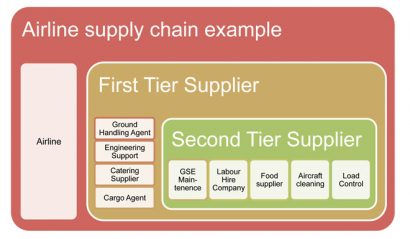

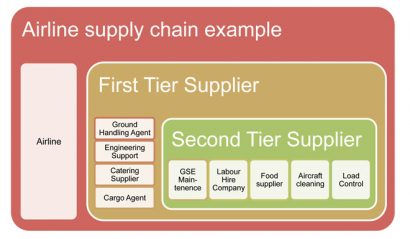

An area of significant growth in the past decade has been the rise of niche ground handling providers. These are organisations that specialise in one particular area to develop an economy of scale that doesn’t exist for an average ground handling agent. This may involve technical tasks that require investment in people, such as providing centralised load control services or flight planning, or the use of specialised ground equipment, such as air starts and de-icing equipment. A niche provider may be contracted directly by the airline (a first-tier supplier) or through a ground handling agent (GHA) (a second-tier supplier) (Figure 1).

(Figure 1)

The ground handling sector of the aviation industry is larger than most people realise. It is often a much maligned department, generally viewed as a bunch of overpaid bag throwers. The reality, however, is starkly different: the industry is evolving with the introduction of new technology redefining the role performed by ground staff. The equipment utilised is highly technical heavy machinery, and staff are required to become more specialised in response to the technological changes. In the Australian environment the ground handling sector comprises 17-18% of all staff employed in aviation1 and the ground handling industry represents 13% of total industry revenue turnover2. From these figures it is clear that the success or failure of the ground handling sector is key to the success or failure of an airline.

Despite this growth and increased complexity, the current practices for management and communication between airlines, airports, and ground handlers have not evolved at the same pace. An airline may say they know who their suppliers are, but does the airline know who is providing services to these suppliers? As a ground handling agent, do all levels of management know who their suppliers are? Failing to understand who is a part of your supply chain can have major consequences. We can look to other industries to see the impact that an ineffective understanding of supply chain management can have.

The risks of no oversight of the supply chain

Supply chain management is a practice that has been formally practised in other industries for a number of years. A clear example of the risk posed by a lack of oversight of the supply chain is demonstrated by the retail industry and their exposure to the unsafe work practices in Bangladesh. In a six month period between November 2012 and April 2013 there were two major disasters in the Bangladesh garment-making industry. On 24 November 2012 the Tarzen Fashion Factory burnt down leaving 117 people dead and over 200 people injured. The building did not have adequate emergency exits, and the building had been designed in such a way that the emergency exits that did exist all lead to a single location, where the fire started. On the 24 April 2013 the Rana Plaza Garment Factory collapsed. The building had been constructed without proper permissions, extended beyond its structural capacity, and used for purposes it had not been designed for. The collapse of this building killed 1,129 people and injured another 2,500.

Both of these incidents were held up as examples of poor facilities for workers in developing nations, and suppliers engaging in behaviour that was dangerous for their workers by not providing them with a safe facility in which to work. The clothing manufacturers in these buildings were manufacturing on behalf of major western brands, and although these brands did not have an active presence in these buildings, their suppliers did. In many instances these were second- and third-tier suppliers (companies that supply goods and services to the nominated supplier). The suppliers operated in facilities that increased risks for workers, and did not have any oversight from the western companies that the clothing was being produced for.

When these incidents occurred in Bangladesh, a number of prominent western companies were made aware that these factories were in their supply chain which forced them to re-evaluate their exposure in Bangladesh and the safety breaches that were the norm. As an example, Walmart were not aware that Tarzen was a supplier until after the fire. As such, they had become exposed to reputational damage risks they had not been aware of. After the Tarzen fire Walmart then undertook a programme to identify who were their second- and third-tier suppliers.

For the aviation industry a supplier undertaking activities that are unsafe presents a much grimmer outcome than reputational risk. Suppliers cutting costs; working in an unsafe manner; or removing quality controls, creates a latent failure that may lead to an incident relating to safety of flight. The concern is where these latent conditions exist within the supply chain, but the airline or ground handler do not know they exist, so no controls have been put into place.

Lessons learned

Looking at the problems that emerged in the Bangladesh fashion industry, there are some key lessons that can be learnt for aviation, and in particular ground handling.

The first lesson is to know who the secondand third-tier suppliers are. In the Bangladesh example, many western companies understood they had outsourced production, but did not understand the provider of the raw materials, or which element of work was then subcontracted again. If we consider the ground handling supply chain, there is a clear relationship between the airline, the ground handler, and the airport. However, having an understanding of the supply chain also includes considering if any work is sub-contracted out by the GHA – this includes aircraft cleaning, receipt and dispatch services, and load control.

The second lesson is that, even where further subcontracting does not occur, consideration must still be given to the supplier of equipment, personnel and management support. Questions must be addressed such as: Who provides the ground support equipment (GSE) that will be used? Is this owned or leased? Are staff employed directly by the contractor, or are they employed through an agency? Even for a ground handler, understanding their supplier is important. Who is conducting maintenance on your GSE? Where do they source their spare parts from? Are they OEM or replicas? Have staff working on or around the aircraft been trained and what was the quality of training? What workload pressures are staff placed under, and is there any ability to ensure they are not fatigued or under-resourced?

What can be done?

A supplier-customer relationship can be one of three types:

- Transactional – where both parties operate at arm’s length

- Collaborative – where both parties cooperate and adjust their business objectives and practices to achieve long-term goals

- Strategic – where both parties commit to an alliance that they share directly in each other’s success.

In a GHA/airline relationship a transactional relationship may be one that exists for the handling of a charter or seasonal flight. A collaborative relationship would be the majority of ‘healthy’ GHA/airline relationships, with both parties making adjustments to ensure long-term service provision. A strategic relationship may occur where an airline and ground handler reach an exclusive handling agreement that provides growth opportunities for the GHA, and perhaps allows the airline greater input into the operations of the GHA.

As a relationship develops the level of understanding of the business of a supplier increases. A supplier will know more about a strategic supplier than a transactional supplier. This knowledge of a supplier helps the organisation to understand what risks may be present and plan to mitigate them as required. This is where, by understanding the nature of existing relationships, extra steps can be put in place to identify risks that may otherwise be overlooked. Following the incidents in Bangladesh, Walmart and other western suppliers were proactive in identifying their suppliers; requiring them to improve the quality of the facilities used to produce goods.

To understand how this can relate to ground handling, consider the following example: A GHA operates in five locations and in each location the local airport manager sources a third-party supplier to provide ongoing maintenance for the GSE. As such, the GHA has five separate GSE maintenance suppliers, who would each be engaged in a transactional relationship. The GHA has no process to ensure that all parts fitted are of the required quality, and does not have insight into the qualifications of the mechanics performing the servicing. This poses some obvious risks, which in turn may be inadvertently passed onto the airline.

There are two main strategies to help improve this situation. The first option is to maintain a transactional relationship, which will keep costs low and allow flexibility to change suppliers, but introduce additional checks for supplier management. This may involve a supplier questionnaire to be used in the procurement phase; a service level agreement stipulating the requirements for parts and personnel; and an oversight programme to ensure these standards are maintained. Alternatively, there may be an opportunity to build stronger supplier relationships by consolidating. Instead of having five different suppliers there may be an opportunity to see if one or two providers can provide a service in multiple locations. Again, this should be supported with a supplier management programme, but this will only require oversight of fewer suppliers who better understand the needs of the organisation.

All too often we see airlines and ground handlers who mistakenly assume that by outsourcing the task they have outsourced the risks and the responsibilities. This is not the case. As the ground handling sector continues to grow more complex, and we see a greater specialisation of skills, we need to remain vigilant to ensure that we continue to identify and eliminate risks within the operation to ensure the safety of both staff and the flying public. Aviation safety starts on the ground.

References

- Transport & Logistics Industry Skills Council, 2013

- CAPA – Centre for Aviation, 2014

I never knew until you shared that GSEs are getting more complex in structure with the recent technological advancements we have in aviation that more staff should be attuned to an aircraft. It makes sense because all the more we should be knowing the flaws and troubles from past plane accidents and this era should come up with better troubleshooting problems, which means series of experts to look into it in precise detail. If I were to own an aircraft, I’ll surely invest in a pool of professional GSEs to watch over and maintain my plane for my passengers’ or customers’ safety.