Keeping baggage safe

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 8 December 2011 | Stefano Dolci, Head of BHS Management, SEA - Milan Airports | No comments yet

The handling of baggage is a very important activity within an airport. One of the main concerns of passengers (and carriers) is to be able to find their baggage on arrival. For this reason the mishandled baggage rate (that is baggage not loaded into the correct plane and shipped afterwards to the passenger) is one of the key performance indicators of the service provided to travellers. Since 2003, the introduction of X-ray screening within all baggage procedures has become even more complex.

It is useful to differentiate between the different types of baggage. They are:

* ‘Local baggage’ that is checked in at the airport

* ‘Transfer baggage’ arrives at an airport on one flight and leaves on another. This is divided into two sub-categories; ‘short connecting baggage’, defined by less than 45 minutes of transfer time, and ‘early baggage’ which incorporates more than three hours of transfer time

* ‘Bulky baggage’, OOG (Out Of Gauge), that exceeds normal dimensions that are not suitable to be sorted with normal conveyor belts

* ‘Special’ items that arrive at the plane with the passenger such as wheelchairs.

There are also implicating costs to consider. The re-routing and shipping of mishandled baggage to its final destination has an average cost of $100. In 2010, 2.44 billion passengers travelled around the world via international airports. In all, there were 29 million cases of mishandled baggage (12 per cent) at a related cost of $3 billion. Europe accounts for approximately 50 per cent of mishandled baggage worldwide and the United States, another 25 per cent (SITA Baggage Report 2011).

The handling of baggage is a very important activity within an airport. One of the main concerns of passengers (and carriers) is to be able to find their baggage on arrival. For this reason the mishandled baggage rate (that is baggage not loaded into the correct plane and shipped afterwards to the passenger) is one of the key performance indicators of the service provided to travellers. Since 2003, the introduction of X-ray screening within all baggage procedures has become even more complex.

It is useful to differentiate between the different types of baggage. They are:

- ‘Local baggage’ that is checked in at the airport

- ‘Transfer baggage’ arrives at an airport on one flight and leaves on another. This is divided into two sub-categories; ‘short connecting baggage’, defined by less than 45 minutes of transfer time, and ‘early baggage’ which incorporates more than three hours of transfer time

- ‘Bulky baggage’, OOG (Out Of Gauge), that exceeds normal dimensions that are not suitable to be sorted with normal conveyor belts

- ‘Special’ items that arrive at the plane with the passenger such as wheelchairs.

There are also implicating costs to consider. The re-routing and shipping of mishandled baggage to its final destination has an average cost of $100. In 2010, 2.44 billion passengers travelled around the world via international airports. In all, there were 29 million cases of mishandled baggage (12 per cent) at a related cost of $3 billion. Europe accounts for approximately 50 per cent of mishandled baggage worldwide and the United States, another 25 per cent (SITA Baggage Report 2011).

When baggage is in transfer the most critical parameter is ‘transfer time’. Carriers tend to reduce transfer times as much as possible (30 minutes between the arrival of the delivering airplane and the departure of the corresponding plane). The handling of these ‘time critical’ items is very difficult and partially explains why transfer baggage accounts for more than 50 per cent of ‘mishandling errors’.

Transfer baggage could be handled in the following ways, depending on the airport infrastructure:

- On to the same sorting system as local baggage

- On a separate sorting system

- Manually on a simple carousel

- Directly, from arriving to the departing plane, also known as ‘tail-to-tail’ baggage. This procedure is normally used for ‘short connecting baggage’ only.

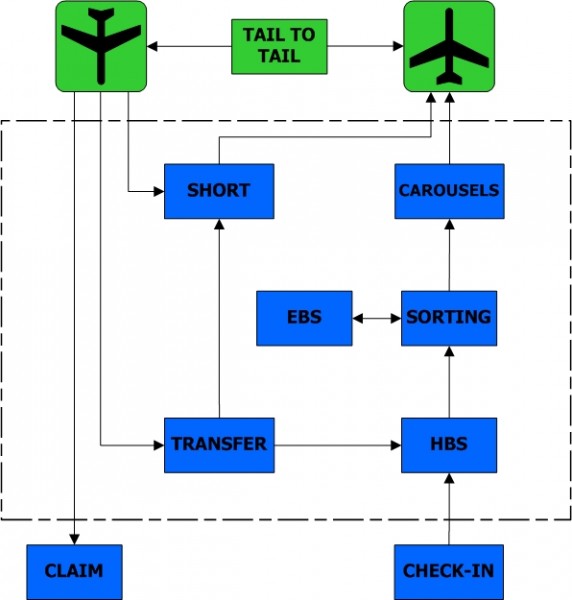

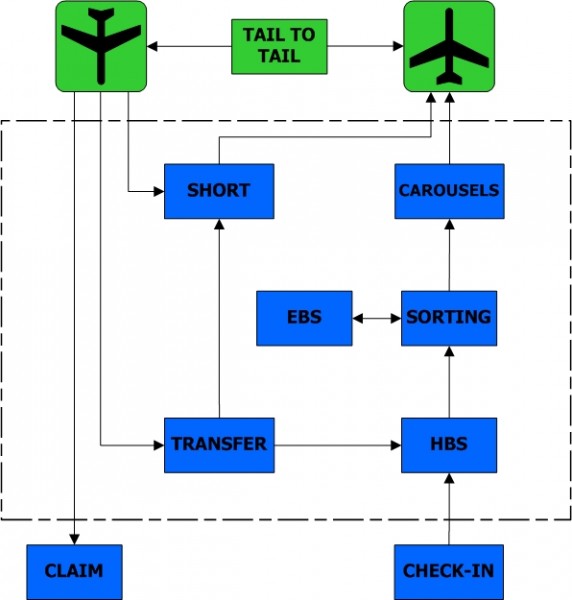

The first solution has many advantages but requires a high capacity baggage handling system with a proper backup administration. A separate system for baggage implies two different make-up points and requires more personnel and additional costs for the system to operate it. The manual sorting of baggage is possible only with very limited volumes and ‘tailto- tail’ procedures, which requires a precise loading of baggage (see Figure 1). This ‘short connecting baggage’ should be loaded in a separate container from the origin airport. Manpower is also required to sort and move items to the correct departing plane. It may also require a car mounted X-ray machine to screen baggage directly on the apron.

FIGURE 1 Typical journey of baggage through an airport

In 2003, X-ray screening became compulsory for all baggage. Until then, only particular flights from Israel and the US were screened. In Europe, security controls within baggage handling are different depending on the origin and destination of the baggage. The handling agent should be aware of the required actions and therefore a suitable monitoring system should be applied.

The introduction of compulsory X-ray screening has added further difficulties to the baggage handling process. Airports have been introducing dedicated screening facilities such as HBS (Hold Baggage Screening) which consists of a number of X-ray machines connected to the Baggage Handling System (BHS) with conveyors belts. These machines are normally located between the check-in desks and the sorting area and are extremely sophisticated and they can cost in excess of €1 million. If an airport has not been able to modify their existing baggage handling system, the X-ray screening takes place within the check-in area.

There is a large range of automated screening systems, with the most complex being a multi-level screening application with different types of incorporated X-ray machines, to the simplest, which requires the manual opening of all baggage.

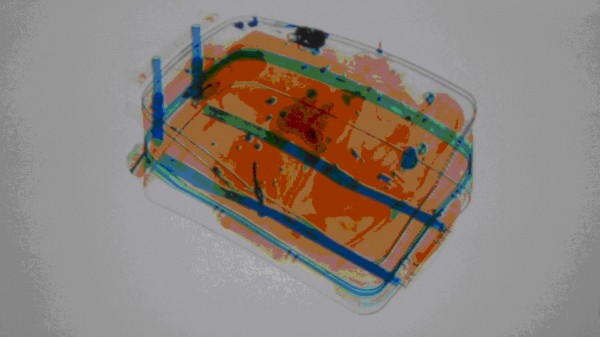

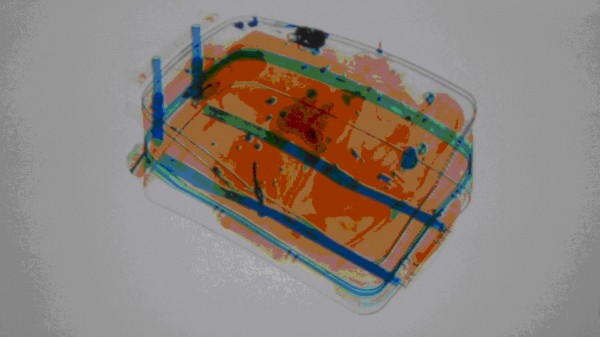

The baggage (see Figure 2), after being checked-in, reaches, via the conveyor belts, the first level X-ray machine (green area) where it is automatically screened. If it is not ‘clean’ (the machine is not able to assure that no prohibited item is inside the baggage) the image (see Figure 3) is sent to an operator at the second level who decides if the baggage is ‘clean’ or not (yellow path). At the end of this path, the decision point is reached (represented by a yellow square). If the baggage is ‘clean’ it is sent to the sorting area, if the baggage is still not perceived as ‘clean’ it is sent to the third level (orange area) where it is analysed again. This time, if the baggage is ‘clean’ it is sent to the sorting system, if not, it proceeds to the manual opening fourth level (red area) where the automated process ends and human checking begins.

FIGURE 2 The most used configuration consists of two different types of X-ray machines

FIGURE 3 An automated baggage screening image

A modern BHS makes it possible to divert baggage directly to the most accurate screening area (the third level). In some airports this third level control is done via tomographic machines, similar to those used within medical environments. To achieve the maximum security level it is important that all baggage can be traced during their way from the check-in counter to the plane hold. Tracing is done with automatic barcode readers (or, in the most advanced baggage handling systems, with RFID readers, as in Milan Malpensa airport) that can scan the 10 digit barcode or chip within the baggage tag and then correlate this with the passenger data message BSM (Baggage Source Message) issued by the carrier when the passenger checks-in. This complete process of tracing the baggage flow allows the airport to improve their baggage handling process and to identify and solve BHS issues, yet it also remains essential to guarantee that every piece of baggage has been properly screened.

A BRS (Baggage Reconciliation System) works within hand held scanners used to read every item of baggage when loaded into the cart or container that will then transport the item to the plane. Another reading will be made when the baggage is loaded into the actual plane hold. The main purpose of a BRS is to assure that no baggage is loaded if the passenger is not on board that specific flight. The way to assure this is to match baggage and passenger data and raise an alarm if, when boarding closes, the passenger is not on board. His or her baggage will then be unloaded before the plane is allowed to move from its stand. Furthermore, as all items of baggage should be scanned before loading, a BRS assures that no incorrect baggage (for example a baggage of another flight) could be on board.

A BRS requires the following IATA standard messages: BSM (Baggage Source Message), BTM (Baggage Transfer Message) and BUM (Baggage Unload Message).

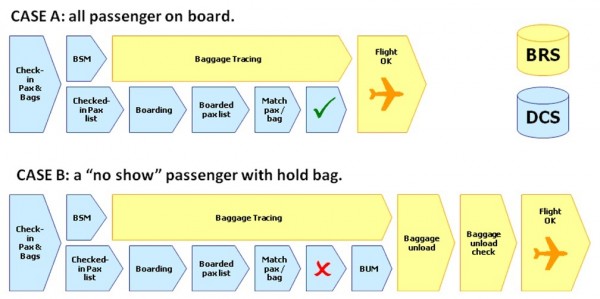

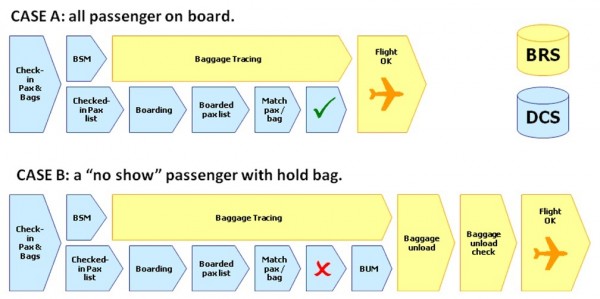

The yellow flow in Figure 4 represents an operation done directly by the BRS while the blue area shows the procedure completed by the carrier DCS (Departure Control System). In case ‘A’ all passengers are on board and the system gets a positive match between the list of passengers and the list of baggage, allowing the flight to be authorised to leave its stand.

FIGURE 4Representation of the process of configuration within two different types of X-ray machines

In case ‘B’ at least one passenger has not boarded the flight that he has previously checked-in for, so the match between passengers and baggage is negative. In this case, the system will be required to unload the baggage and to read it again for confirmation. Only then, will the flight be authorised to leave the stand and take off.

The BRS is also used to trace baggage even after the items have passed through the BHS or to trace particular baggage such as wheelchairs, strollers etc. Whilst a normal bag is automatically sent through the X-ray screening by the BHS, an out of gauge item is usually handled manually and must be scanned when delivered to the dedicated desk. The BRS will not allow the operator to load it into a cart if there has not been a previous reading made by a security officer which states that it has been positively screened.

In the same way a stroller, which is used by the passenger until reaching the gate, must be read with a hand held scanner at the security checkpoints where the security officer will manually check the item. Only after this reading can the handling personnel receive the item from the passenger at the gate and then load it into the plane.

Even in the most difficult cases a BRS can assure that security has been guaranteed, fulfilling all law requirements and meeting IATA standards. For example, a passenger coming from an airport may be unable to print the boarding pass for the second leg of the journey but requires baggage to be tagged to their final destination. The passenger has not been checked-in for the second leg of travel and should get the boarding pass during his or her transfer time, meaning that he or she will not be on the boarding list until the new boarding pass has been printed. The BSM will account for this possibility giving the authority to load only after the second check-in has been completed.

Besides having primary security features, a BRS could be developed to help the handling agent to improve baggage handling operations. The BRS can help workers by advising which container an item of baggage should be loaded into as well as providing operators and the carriers with information about the quantities of loaded baggage and of baggage that has not yet arrived at the make-up point.

Ultimately, the level of disruption to passengers needs to be kept to a minimum ensuring smooth passenger flow throughout the important security checks. In 2011, this is now the norm.

About the Author

Stefano Dolci works for SEA – Milan Airports in the Operations Department. He is the head of Baggage Handling System Management and is also responsible for Maintenance at Malpensa airport. Mr. Dolci has experience in new technologies. He is the Project Manager for the RFID installations at Malpensa and for the development of the Automated Baggage Reconciliation System.